How Movement Becomes a Tool for Design

By Sara D’Amato, Intern Architect OAA

Architecture is often understood through drawings, models, and digital simulations. But long before a design becomes a physical object, it is experienced as movement: the turn of the body at a corner, the rhythm of steps down a corridor, the shift of weight as someone looks out a window.

For architect and choreographer Sara D’Amato, these embodied responses are not simply by-products of design. They are powerful sources of insight. Through her research project Choreographing Architecture, she explores how movement, improvisation, and choreographic notation can generate architectural ideas and reveal new ways of understanding space.

Beginning with the Body

Sara’s work starts with somatic movement principles: paying attention to how the body reacts to the built environment. Rather than beginning with a plan or section, she begins with the body’s lived experience. How does it lean, twist, pause, or reach in response to a room? How do these instinctive gestures reveal spatial intention?

This awareness forms the foundation of a method where the body becomes both the subject and the tool of design.

Learning from Choreographic Precedents

The research is grounded in an intriguing lineage of choreographic and architectural experimentation.

- Bernard Tschumi’s Manhattan Transcripts translate urban experience into sequences of movement and event.

- William Forsythe’s choreographic systems consider movement as a generative rule set, creating spatial possibilities that extend beyond the stage.

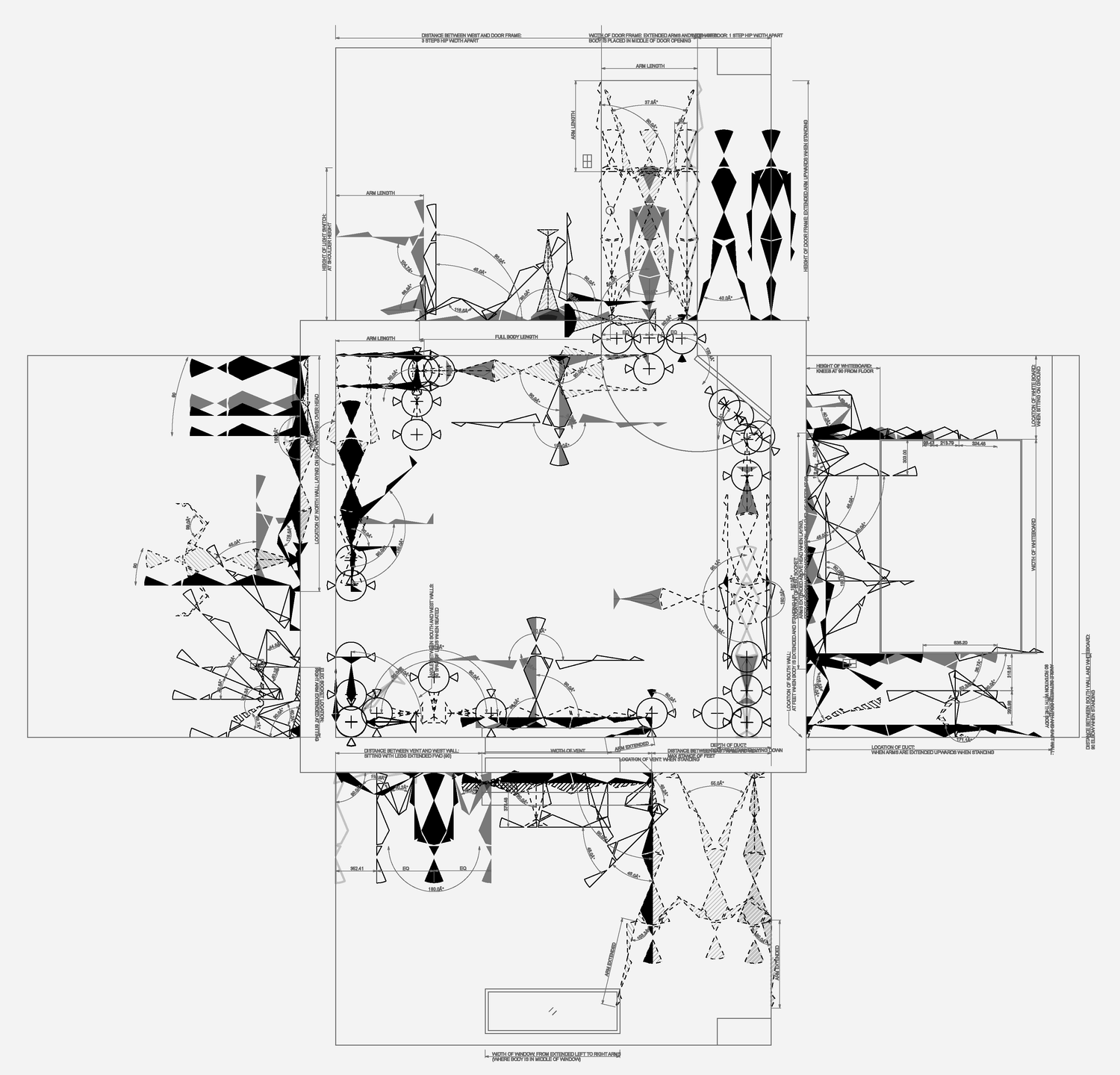

- Eshkol-Wachman notation, a geometric language of joint articulation, maps movement with mathematical precision.

Sara’s work acknowledges both the strengths and limitations of these systems. While they offer rigorous ways of recording human motion, many depend on rule-based languages that require specialized training. Her goal is to bridge the gap between intuitive movement and architectural application.

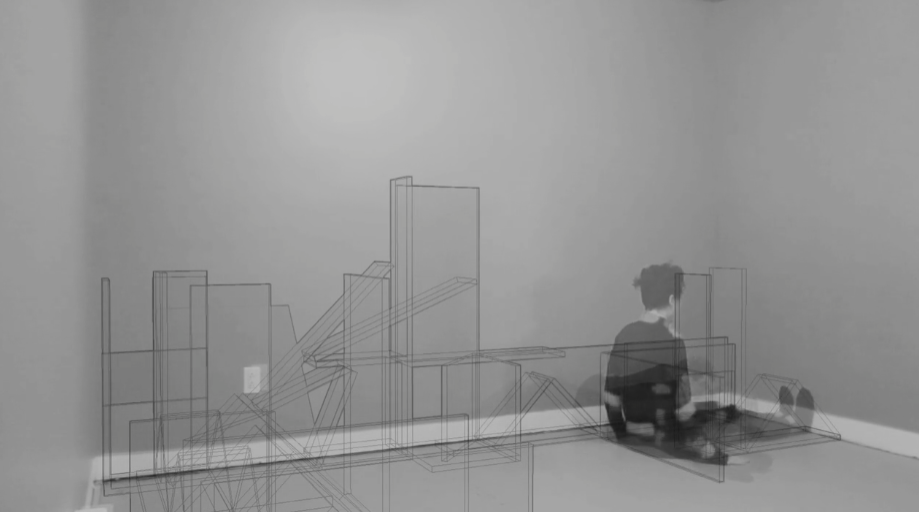

Movement Scripts: Generating Form Through Gesture

A central component of the research is the development of movement scripts: graphic records of gestures, alignments, and improvisational sequences. These scripts are created through:

- Distortions:

Sara dances within an empty room, responding to walls, apertures, corners, and height. Each movement is recorded as both a choreographic notation and a spatial diagram. These notations are then translated into geometric forms, layering movement into architectural massing.

- Permutations:

The movement-based rules are applied in new sequences, independent of the original room. This produces unexpected geometries, distortions, and spatial relationships. Improvisation becomes a design engine.

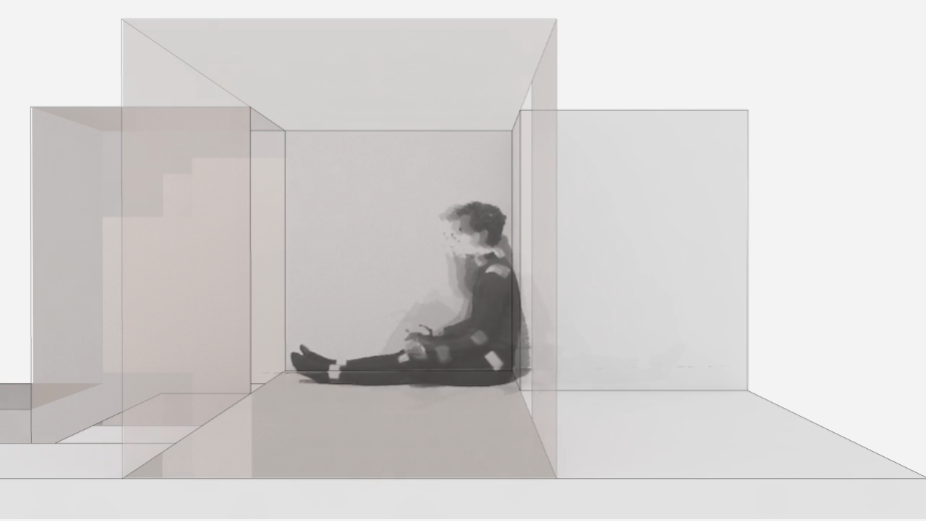

- Activities:

The process reverses. Sara re-enters the geometry and performs imagined domestic actions within it. Cooking, sitting, reaching, resting. These actions reveal new movement paths and reshape the spatial construction.

Across these stages, movement is not used as metaphor. It is a direct generator of form.

Reimagining Space Through Embodied Experience

The research raises essential questions for architecture:

- What if early design thinking began with how the body wants to move, pause, or engage?

- How might spatial sequences change if they emerged from improvisation rather than strict programmatic constraints?

- How can embodied movement reveal biases, habits, and overlooked assumptions in the design process?

In a discipline often dominated by digital tools, Choreographing Architecture offers a rare return to the body as the origin point.

Why This Matters for Practice

For our studio at BNKC, Sara’s research expands how we think about space at every scale. Whether refining circulation, designing public thresholds, or shaping residential interiors, movement becomes a lens that deepens our understanding of user experience.

Her work reminds us that design is never only visual. It is physical, interpretive, and iterative. Spaces are not just drawn. They are inhabited, navigated, and felt.

Toward an Embodied Design Toolkit

As Sara continues this research, she is developing a set of tools that merge choreography with architecture:

- Generative rule sets for movement-based form making

- Notation systems adaptable to early design diagrams

- Methods for translating somatic feedback into spatial concepts

- Approaches to using improvisation in studio workshops

These tools aim to support more responsive, human-centered environments and to offer designers new ways to explore atmosphere, sequence, and emotional resonance.

A Closing Reflection

At its core, Choreographing Architecture reframes design as an embodied practice. It asks architects to not only draw space, but to move through it, feel it, and understand the many ways the body already knows how space should behave.

It imagines a future where choreography and architecture inform one another in richer, more intuitive, and more humane ways.